- Home

- Dan Pearce

He Who Cannot Die Page 20

He Who Cannot Die Read online

Page 20

I hadn’t had the chance to check on the state of my affairs before leaving home. I pulled up the website of each institution with which I banked and made sure my accounts were all still intact and accessible. This took some time as there were many of them. I had quite a bit of money stashed in banks all around the world, under many different identities, and had long before setup a system to get to them at any time should I find myself displaced or in need of escaping. Most of my balances showed a big number with a minimum of two commas and six digits trailing it, but many of the accounts showed numbers and commas and digits reaching much higher than that. Nobody on Earth knew just how much money I had accumulated over such a long period of time, or the lengths I had taken to move it all around and hide it all from ever being tracked to me. Life was hard enough without other people knowing I had such ridiculous access to cash.

Money is such an interesting thing. I have always had a love-hate relationship with it, especially once it was created more officially in the form of coins and later in the form of paper. I have been around since money existed only as obsidian, and the troubles I have seen lucre bring to any individual person, or the people with whom that person associates, have far exceeded the goodness I have seen come of it. I have fought or suffered through many wars which were started because of money. I have seen countless friendships and relationships destroyed because of it. I have watched promising futures thrown away in its pursuit. I have seen many of the greatest evils become common because of money as well. I have seen it cause people to be resentful, distrusting, and greedy. Greed is such an ugly thing. It has always been fed most by money. And rare is the person who can ever seem to have enough money, no matter how much that person has accumulated.

I have also seen many great things come to pass because of money as well. I have seen cures develop for illnesses which once had the ability to wipe out large portions of the population. I have seen money fund so much innovation, which has led to incredible forms of transportation, communication, and quality of life for people around the entire world. I have seen those with much of it give, and build, and create better lives for those with none of it. I have seen those with little of it give to those with even less of it. I have seen family members and friends freely share it with one another in times when money means the difference between survival or not. I have watched the masses come together to stockpile enough money to help individuals or to help individual causes. I have seen it push people to be caring, thankful, and generous. Generosity is such a beautiful thing. It has always been fed by money, and by those who understand that giving away a portion of their excess is only a good and positive thing for everyone involved. Rare is the person who can ever seem to stop giving, no matter how much that person has given.

I have no desire to prove to anyone my own relationship with money, or how often I find ways to give my money to others. I have long believed a person must only come to know another person’s true character in order to know whether that person is more often driven by greed or inspired by generosity when it comes to their money. Generous people ooze an overwhelming feeling of generosity from their entire auras. Greedy people ooze an equally overwhelming feeling of greed. A person’s energy surrounding money really cannot be faked.

Although it is so common, I have always been saddened as I watch good and smart people struggle with money. Money is such a damned easy thing to find once a person understands how it works and just how much of it actually exists in this world. Money is always within grasp for anyone who is willing to think ahead to a place beyond their current difficult relationship with money, and believe they are worthy of having a sufficient amount of it.

These are thoughts in which I get lost any time I check my accounts, which is something I do as infrequently as possible. I am one who likes to forget my money exists until I have a very good reason to think about it.

Once I had finished checking each of my banks, I moved on to my brokerage accounts. It is embarrassing how much money is sitting in each of those. I pulled open the account I secretly opened using Samantha’s name and social security number long ago. I knew she was an incredibly intelligent woman, and that she would be more than okay financially if I did nothing for her should I ever disappear, but I had never been a man who could knowingly leave a person I love without some sort of added security from me. Her account was in order, and there was enough there to last any reasonable person three lifetimes. I knew Samantha would likely give much of it to help her struggling family members or friends. Money never had driven her, and she never once asked me how much money I made or had stored away in the ten years we had known each other. This particular account was my just-in-case fund for the woman I loved, and my estate attorney knew exactly what I wanted done with it should I ever suddenly vanish.

Electricity. The Internet. All of technology. If for some reason I did lose Samantha, this would be the easiest time I have ever had being able to somehow continue taking care of those I left behind. Before Samantha, and before the age we currently lived in, I had to go to great lengths to make sure the people I loved were taken care of after I was no longer part of the picture. I had to employ the help of trusted people and form walls of secrecy that would never let those I loved know it was from me. Nowadays all of it is done through encrypted data connections and from behind firewalls. Few humans have to ever be involved with any of this at all, and with the click of a few buttons I can move massive amounts of money and assets around like they were Monopoly pieces on a game board.

It is true that I have always taken care of those I left behind, especially since I lost my Annia. If there were children involved since her, I made sure they were cared for just as fully. I certainly don’t share this to toot my own horn by any means. I share this to simply mention how important it has always been to me, and more importantly how hollow a gesture it strangely somehow always seemed. There never was a time for me when I felt money or things were a sufficient replacement for my disappearance. Never once did I think money or things would make things better for those left coldened by the shadows of loss. I just gave money or things to them because there really has never been a whole lot more that I could do; not without running the risk of accidentally communicating or letting them know I was still out there. To do so would mean sudden and immediate death for someone I loved very much, and so I stuck to money and things, covered-up by stories that would make strange but perfect sense.

In preparation for doing just that for Samantha, I sent-off a quick email to my attorney, informing him that he should check in on me in eight days’ time. If I didn’t answer him back, he was to put into motion everything I had setup for her. I sincerely hoped things wouldn’t come to that, but I wasn’t going to avoid putting everything into place based on a game-plan of hope. I knew there was a very good chance this trip to Peru would end fruitless, just as every other attempt to find Tashibag had always ended.

Once that email was sent, I logged into my Facebook messages. Zhang had finally replied. Tereza still hadn’t. Zhang knew nothing which could currently help me find Tashibag, but he told me of a secret society made-up of Tashibag’s cursed, which had been heavily attempting to recruit him. I had seen groups like this pop-up before and didn’t put much thought into it as it had no effect on the task at hand or the current deadline which faced me. The only part of his message which gave me pause was the number behind it. Zhang said more than 40 now were part of the secret society, a number far greater than any number in the past. I quickly sent Zhang a message of thanks and promised to get back to him after my current journey ended.

Having wrapped-up every loose end I could think of, I jammed my laptop into its bag, downed the rest of the Peruvian corn chips I had been working on, and made my way to customs to find my suitcase. From there, a taxi driver got me to the travel station, and an hour later I was sitting on a bus amidst a crowd of dirty and poor Peruvians, their chickens, their dogs, their bicycles, and their goods, all headed to the small town of Oco

ngote, where Ashwin believed Dishon to currently be.

Realizing it would come in handy, I pulled out my iPad Pro and my Apple Pencil and began sketching a portrait of Dishon completely from memory. A young boy knelt beside me as I drew it, completely captivated as my swoops and slashes began forming into a picture of a man whose face I knew from memory better than any other. When finished, I just looked at the portrait for the longest time, thinking of Dishon, and of the last time we had seen each other, and of so many of the adventures we had shared together over the millennia.

The iPad sat glowing in my lap. The boy who said nothing, but gazed at me intently and with great curiosity, repeatedly turned his attention from my face to my art and then back to me again. He really wasn’t much different than I had been as a child. His parents possessed almost nothing. His only clothes were likely the filthy worn rags he was wearing. He was dirty, and life for his family was focused on survival before anything else. In just a decade and a half, I had grown accustomed to always having incredible electronic gadgets with bright screens in my pockets or tucked under my arm. In just a few decades I had grown accustomed to flying great distances at incredible speeds, thousands of feet above the same ground I once wandered for centuries. In just the past century I had grown accustomed to driving manmade roads in manmade cars which moved so quickly and so gracefully.

Every new year that passes has brought amazing advancements to those like me who are fortunate enough to have whatever it has always cost to work those new advancements into their ways of life. Whether it was badger skins or dollar signs on a computer screen, the world has always offered a better way of life to those who could afford it. For everyone else, like this boy and his mother who sat nursing an infant on the seat across from me, the world offered very little, and it hadn’t changed much at all for them even over thousands of years.

Dishon’s curse was to watch the world advance and progress, and to never be allowed to advance and progress along with it. Even though he could not die, he still had to beg to survive. He still had to work for scraps of food. He still had to live with those who lived in the dirt, filthy and destitute.

That same divide which grew exponentially between the advancement of mankind and the stagnation of mankind is what ultimately separated Dishon and me. There came a time when the world had advanced enough, and working together became inefficient enough, that the only logical choice was to go our separate ways. We fought the phenomenon far longer than we should have, but in the end, I had to choose between living with nothing and living up to my potential. This is, and always has been, the sad reality for all of mankind for as long as we have existed.

If it weren’t for the iPad I zealously held up to the faces of the poor once I arrived in Ocongote, I felt in many ways that I was back to a place where my roots so often called-out to me, begging me to return more often in order to remind myself just what a life without extreme wealth and technology had once been.

It didn’t take long to find someone who recognized Dishon’s portrait. A young boy pointed me in the direction of the street he had seen Dishon begging in recent weeks. The boy led me to the corner where he last saw Dishon, but my friend wasn’t there. A man pushing a food cart looked at the portrait on my iPad and informed me he had seen my friend arrested two days earlier, and that Dishon was likely locked-up in the small city jail in Checacupe, just a couple towns over. I asked why Dishon might have been arrested, but the information this man had to give me was limited.

His limited information, and a rather talkative taxi driver, led me to the jail; Dishon indeed had recently been incarcerated there. The jail consisted of one tiny rusted cell taking up nearly all of what looked to have once been a family’s one-room cinderblock home. A guard who reeked of decades’ worth of booze sat on a failing folding-chair outside the jail, snoozing away his afternoon hangover. I poked him until he awoke and handed him a cold bottle of water which I had purchased at the corner store just in case having his nap interrupted upset him. The guard groggily took a look at the portrait on my iPad. As if I had plunged a needle full of adrenaline into his heart, he leapt to his feet and began ranting to me, demanding to know what I knew about the man who had escaped from his jail cell the night before. He showed me the empty cell and insisted the lock had never been opened, and that no other way of escape was possible. Dishon obviously hadn’t escaped. He had been displaced for sleeping in the same place twice, but I couldn’t tell the guard that. Instead I assured him that if I could find the man, I would return him to the jail immediately. It was this false promise, along with a hundred bucks to keep him from taking my iPad as “evidence,” that finally calmed the guard.

Having no idea where Dishon had ended-up from there, I hired another taxi driver to take me back to Ocongote, where I hoped Dishon would somehow show up again. He was obviously in that city to begin with because it was the place he knew he needed to be. I knew my friend enough to know that he would always be in whatever place he thought would lead him to Tashibag. Dishon could not possess any physical thing, but he could hold onto a purpose and a mission, and so he always held onto the two things that couldn’t be taken from him as if he were holding onto diamonds or gold.

My friend had already returned to Ocongote before I could get there. I arrived just as dusk set-in and the rubbish-filled streets of the small city began to glow with manmade light.

While still some ways down the hill where the taxi had dropped me at my lodgings, I recognized him by his shadow only. I knew it was Dishon, drunk off his ass, begging passerbys for anything they would give him as they entered and exited a shoddy neighborhood bar. Apparently, he wasn’t the only one who knew the shape and appearance of an old friend all too well. “I know that shadow anywhere,” he suddenly called to me as I approached him, still obscured by the darkness that had taken over the thoroughfares of Ocongote. “And your terrible smell is overpowering, you old gorilla.”

I laughed at the stupid joke I had heard him make dozens of times before, and we embraced the same way we had so many times in centuries and decades past. Even though life had eventually separated us, our friendship had never been damaged by it. There was too much history and too much between us to ever have a falling-out or lasting hurt feelings. Dishon knew the reality of life as much as I did, and he never held it against me that I eventually couldn’t stay by his side.

I ordered us a table inside the bar, and once inside I instructed the very drunk Dishon to order whatever he liked, and to start with water. He obliged. Once he quickly drank that, I ordered him a coffee. He eagerly gulped-down several cups of it while we waited for our plates of ceviche to arrive. “So tell me, why did my journeys to find my oldest friend take me to a jail cell?” I asked, giving him a friendly poke in the ribs.

Dishon looked intently at me, his eyes bloodshot and tired and only half-focused. His clothes were slick with grime and filled with rips and tears. He wasn’t as skinny as some of the other times I had found him, but he was far from healthy. “Cain, you know why.”

“I do?”

“Of course, you do.” He tapped his mug at the waitress indicating he wanted a refill on his coffee.

I shrugged my shoulders. “How could I possibly know?”

He just looked at me with those same eyes that had such diminutive amounts of life left in them. “I was hungry, Cain. I am always so fucking hungry.”

“Say no more,” I told him. “Let’s get you fed and get you a real bed for tonight.”

CHAPTER 18

I left Dishon in my motel room, if it could be called that, to sleep the alcohol out of his system while I went in search of new clothes for him that didn’t look as if they had been pulled from the throat of a rotting dead Pitbull. I returned a couple hours later with a red and black-striped polo shirt and a pair of pants which seemed to be half-khaki half-denim. I purchased a pair of long white soccer socks and a couple of used Adidas sneakers that looked like they would probably fit him.

I held th

e new clothes out to Dishon when I returned, who was somewhat sobered and fully awake. “I couldn’t find any new underwear,” I told him. “We can look in the morning.”

“Thank you,” he said then cleared his throat. “Put ‘em down on the bed.”

I did as he instructed, feeling silly that I hadn’t remembered how this exchange needed to happen.

“I stopped wearing underwear long ago,” Dishon grunted as he began stripping naked. “I don’t know why I ever started wearing it in the first place.” The grime which covered his body was a different kind of grime than what I had seen cover him in the past. It was so thick and so greasy that I could barely make out the mark which Tashibag had placed upon him. Now completely nude, he held out his disrobed and wadded clothes as well as the flaps and layers of materials he called shoes. “Cain, I give you my clothes. They are yours now,” he said.

“I accept them as my own. My desire is for you to have these new clothes,” I said, pointing to the clothes on the bed. This was the process we had always followed to keep any new clothes from disintegrating when he took hold of them. Dishon held up the polo shirt in one hand and the soccer socks in another, then looked at me to ask if I was serious. “It was the best I could do in a place like this and at such a late hour,” I said.

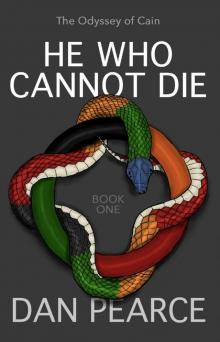

He Who Cannot Die

He Who Cannot Die